Persecution and the development of Yezidi ritual life

Eszter Spat

Syncretism

There is another aspect of the impact the ISIS attack had on ritual life within the Yezidi community, one which perhaps merits mentioning: a fascinating “internal syncretism”. Despite their common roots and a more or less constant contact, through the centuries the two communities have developed their own distinct customs and rituals. The enforced mixing of the two groups, however, may eventually lead to their adopting each other’s traditions, enriching their religious life and giving it new layers. It also makes Yezidis aware of how varied their own traditions are. In the past decades, the process of scripturalisation and the introduction of religious education at schools, complete with centrally produced books, have gradually been leading to the eventual uniformisation of a previously multiform tradition and to the acceptance of the notion that there must be “a right form” of texts, rituals and holidays. At such a time, experiencing first-hand the various differences may have a great effect on how Yezidis think about their religion and may counterbalance the simplified view provided by books (and recently television programs) on the Yezidi religion

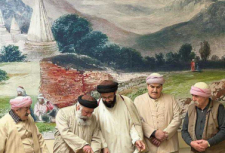

Yet another curious difference between the ways holidays are celebrated in Sinjar and in the Kurdish Region concerns the discrepancy between the holiday cycle of the feqîrs and the holiday cycle of everybody else. Feqîrs were originally men of religion, or men who opted to live a life of asceticism. However, in the course of the nineteenth century, feqîrs in Sinjar evolved into a special community organised along tribal lines (Fuccaro, 1999: 30). Though they are no longer men of religion (except for the few who opt to don the xirqe and live the life of an ascetic), feqîrs still occupy a special niche within religious life. All the males wear beards, just like Yezidi men of religion, and older feqîrs allegedly pray twice a day. In the past, there were many qewlbêj or “sayers of hymns” among the feqirs of Sinjar, while others (both males and females) knew many prayers (duʿa) for curing various ailments. Feqîrs also observe their own calendar of holidays. Some holidays (like the Holiday of Şex Alê Şemsa) are peculiar only to the feqîrs, but even more interestingly, for some no-longer remembered reason, feqîrs celebrate all the shared holidays a week before others. This is a fact that most Yezidis living in the Kurdish region were formerly not cognizant with, since most feqîrs live in Sinjar these days. In the spring of 2015 many locals witnessed feqîrs celebrate New Year in style: go on a pilgrimage to Lalish just before New Year, then on the day of New Year mourn at the graves of those who passed away after the flight from Sinjar and were buried in local cemeteries, sacrifice a sheep, prepare a holiday lunch for the extended family, and receive visitors proffering their good wishes for new year – one week early. Similarly, a week before locals celebrated Holiday of Êzîd or Bêlinda, feqîr families duly repaired to the graves to consume some holiday food there or to light bonfires. Again, some of these feqîr families were accompanied by their local friends or relatives58 on these occasions.

Tags: #yazidisinfo #ezidi #aboutezidi #traditions

Persecution and the development of Yezidi ritual life

Eszter Spat

Syncretism

There is another aspect of the impact the ISIS attack had on ritual life within the Yezidi community, one which perhaps merits mentioning: a fascinating “internal syncretism”. Despite their common roots and a more or less constant contact, through the centuries the two communities have developed their own distinct customs and rituals. The enforced mixing of the two groups, however, may eventually lead to their adopting each other’s traditions, enriching their religious life and giving it new layers. It also makes Yezidis aware of how varied their own traditions are. In the past decades, the process of scripturalisation and the introduction of religious education at schools, complete with centrally produced books, have gradually been leading to the eventual uniformisation of a previously multiform tradition and to the acceptance of the notion that there must be “a right form” of texts, rituals and holidays. At such a time, experiencing first-hand the various differences may have a great effect on how Yezidis think about their religion and may counterbalance the simplified view provided by books (and recently television programs) on the Yezidi religion

Yet another curious difference between the ways holidays are celebrated in Sinjar and in the Kurdish Region concerns the discrepancy between the holiday cycle of the feqîrs and the holiday cycle of everybody else. Feqîrs were originally men of religion, or men who opted to live a life of asceticism. However, in the course of the nineteenth century, feqîrs in Sinjar evolved into a special community organised along tribal lines (Fuccaro, 1999: 30). Though they are no longer men of religion (except for the few who opt to don the xirqe and live the life of an ascetic), feqîrs still occupy a special niche within religious life. All the males wear beards, just like Yezidi men of religion, and older feqîrs allegedly pray twice a day. In the past, there were many qewlbêj or “sayers of hymns” among the feqirs of Sinjar, while others (both males and females) knew many prayers (duʿa) for curing various ailments. Feqîrs also observe their own calendar of holidays. Some holidays (like the Holiday of Şex Alê Şemsa) are peculiar only to the feqîrs, but even more interestingly, for some no-longer remembered reason, feqîrs celebrate all the shared holidays a week before others. This is a fact that most Yezidis living in the Kurdish region were formerly not cognizant with, since most feqîrs live in Sinjar these days. In the spring of 2015 many locals witnessed feqîrs celebrate New Year in style: go on a pilgrimage to Lalish just before New Year, then on the day of New Year mourn at the graves of those who passed away after the flight from Sinjar and were buried in local cemeteries, sacrifice a sheep, prepare a holiday lunch for the extended family, and receive visitors proffering their good wishes for new year – one week early. Similarly, a week before locals celebrated Holiday of Êzîd or Bêlinda, feqîr families duly repaired to the graves to consume some holiday food there or to light bonfires. Again, some of these feqîr families were accompanied by their local friends or relatives58 on these occasions.

Tags: #yazidisinfo #ezidi #aboutezidi #traditions